- Post authorBy Steve Haworth

- Post dateSep 19, 2023

- No Commentson Tweed suits to Gore-Tex

The evolution of ramblers and their gear.

Times have changed since that early Lakeland fell walker, William Wordsworth, “wandered lonely as a cloud”.

Today he wouldn’t be so lonely, as the popularity of rambling has never been higher. He would also be amazed how walking has become big business and perhaps bewildered by the number of outdoor shops and on-line retailers and the variety of gear they offer.

In this post (Part 1), I trace the history of walking for pleasure in the UK. Along the way we’ll meet Romantic Poets, Kinder trespassers, disciples of Alfred Wainwright and the most recent species of walker, pandemic perambulators. In a companion post (Part 2) I describe how the clothing and equipment of walkers has changed since William took a ramble round Grasmere.

18th and 19th Century – A pursuit of (romantic) gentlemen and a few formidable ladies.

Not many folks walked for pleasure in the mid-18th century. Walking was considered impractical and unnecessary for the rich and poorer people didn’t have the energy or leisure time for it after a day’s hard graft in field or factory. Towards the end of the century though walking began the transition from a necessity to the enjoyable leisure activity it is today.

Wordsworth is often cited as the first to popularise walking for pleasure, but in fact a Scottish priest beat him to it. In 1778, Thomas West published “A Guide to The Lakes”: his book was a huge success and began the process that made the Lake District the tourist mecca it is today. So, next time you’re sat in a 15-mile tailback on the M6, you know who to blame.

I don’t know if West was a romantic soul, but Wordsworth certainly was. In the mid-18th century The Romantic Movement began to influence perceptions of the outdoors: they contributed significantly to the idea of walking for pleasure by promoting an appreciation of nature and encouraging people to explore their surroundings on foot.

The Romantics believed people had lost touch with the natural world and attributed this to two factors. Firstly, the movement was a reaction to the science-focussed philosophical “Age of Enlightenment” and secondly a political response to the cold, manufacturing-focussed Industrial Revolution. They believed a person’s true self could be found only in the wilderness, not in the urban sprawl. I’ve found they speak of nothing else in the Dog and Gun in Keswick after a few pints of Loweswater Gold.

Wordsworth certainly liked a good walk; sometimes on his own, but often with his sister Dorothy (of whom more later) and his fellow Romantic poet and Lakeland neighbour, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He was often inspired to write poetry on these walks, not just in the Lakes but also, at the age of 20, on a long walking trip across the continent (his autobiographical “The Prelude”), a later walk around Wales (“Tintern Abbey” in the Wye Valley) and on a year-long sojourn in the Quantock Hills in Somerset with Coleridge and Dorothy (The Lyrical Ballads). As well as poems, his hike across France also produce an illegitimate daughter, Caroline, so hiking clearly wasn’t the only exercise he enjoyed.

Later, in 1799, he undertook a three-week walking tour around the Lake District with Coleridge. The accounts of their tour did much to stimulate members of the public to emulate their adventures, but maybe not as much as his “A Guide through the District of the Lakes”, first published in 1810 but best known from its expanded 1835 fifth edition. After this, Wordsworth’s reputation as a populariser of the Lakes was assured.

All of Wordsworth’s poems, together with his descriptions of the beautiful landscape and the joys of rambling through it, clearly influenced others and promoted the idea of walking for pleasure: however, those they influenced were from the upper echelons of society. In Wordsworth’s day, to take off for a walking tour or even a day’s ramble you had to have both the leisure time and the money, both of which were denied working men and women.

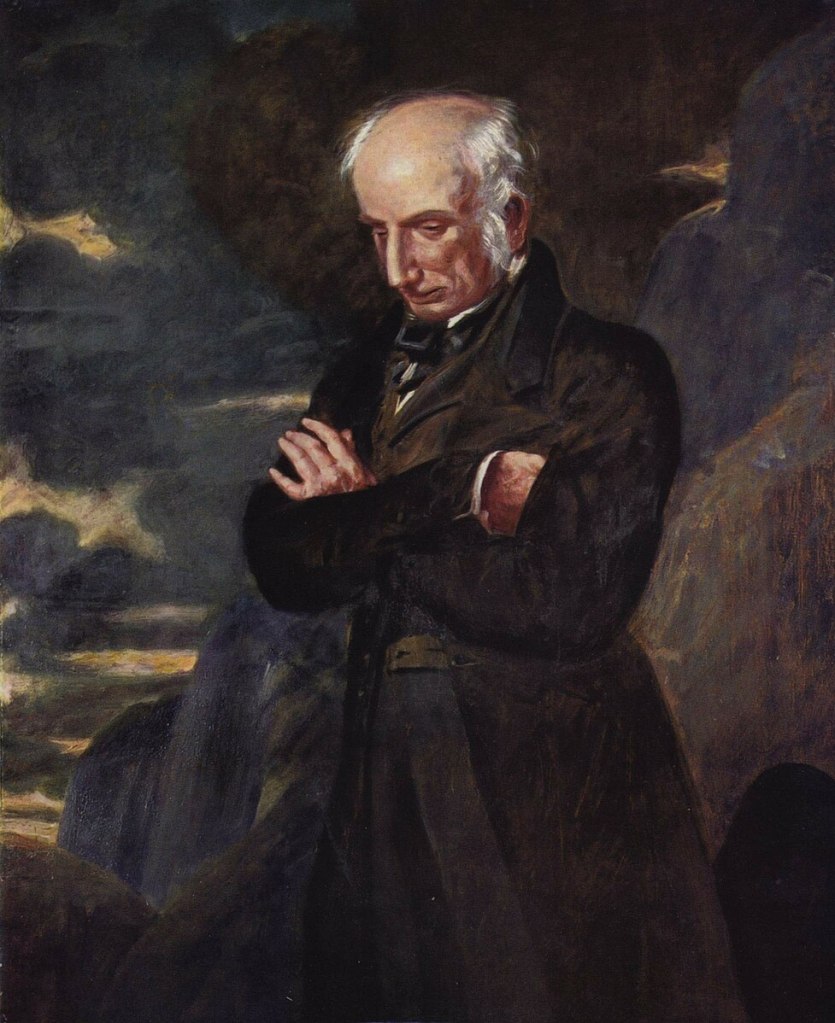

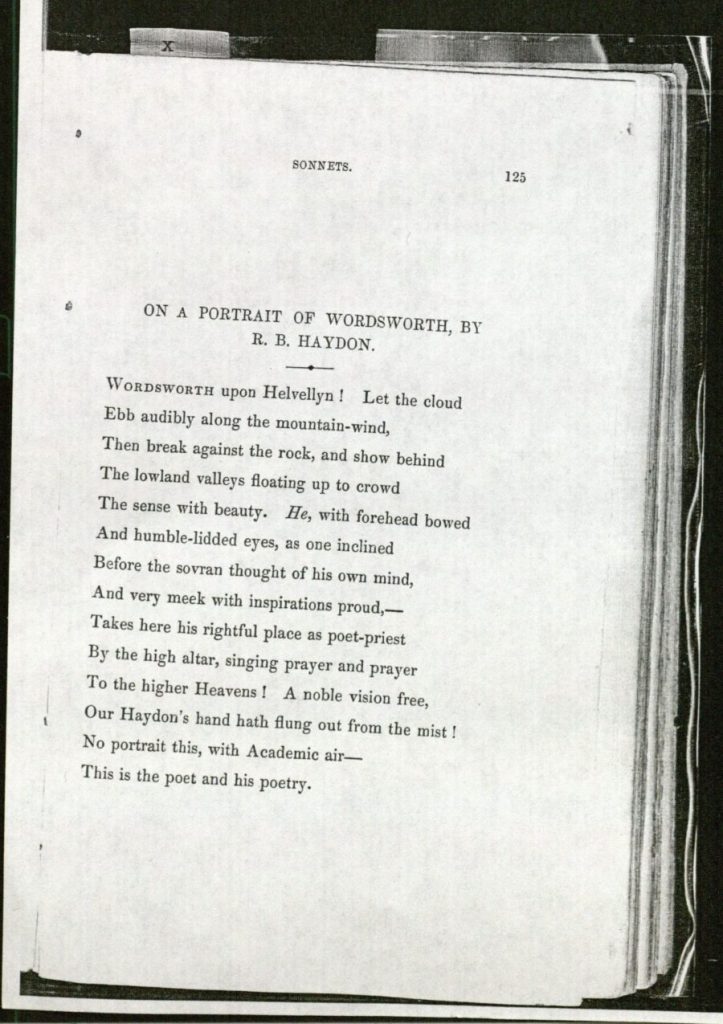

Wordsworth walked all his life, which was a relatively long one for those times. In a comic article from 1839, Thomas De Quincy estimated that he “must have traversed a distance of 175,000 to 180,000 English miles”, despite having “unshapely legs”. Unshapely or not, his legs carried him to the top of Helvellyn at the age of 70: this feat was commemorated in the painting, “Wordsworth on Helvellyn”, by Benjamin Robert Haydon and the sonnet that Elizabeth Barret Browning was moved to write after seeing it. If you ask me, the old lad doesn’t look desperately happy to be there, but that’s maybe due to chafing caused by the rather formal tweedy attire he’s wearing?

Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy was a formidable woman and more than a match for William on the hills. Her “Grasmere Journal” documents the years she lived with her big brother in Dove Cottage and records that they walked almost every day. In 1818, when she was 46, she boasted that she could “walk 16 miles in 4 ¾ hours, with short rests between, on a blustery cold day, without having got any fatigue.”

She was also far more than a sedate, lowland rambler; indeed, Joanna Taylor, a Wordsworth scholar from Manchester University, describes her as “the Wordsworth who put mountaineering on the map”. In the same year that she boasted of her endurance, she climbed Scafell Pike with a female friend. This was one of the first written accounts of a recreational ascent of a mountain and certainly the first to be written by a woman.

It is hard to exaggerate just what a revolutionary feat Dorothy’s forays up the high fells were, at a time when women walking by themselves anywhere was frowned upon. As Taylor observes, “their climb was a rebellious act that opened up mountains for successive generations of women”.

Leaving the first generation of rambling Romantic Poets and moving into the 19th century we find that hiking remained essentially a pursuit for the better off, although during this period some working class people did start taking to the hills to escape the pollution and stresses of daily life in the rapidly industrialising cities.

Around this time the next generation of Romantic Poets continued to be inspired by walking in wild open spaces. In 1818 John Keats took a walking tour of the Lake District and Ireland and later, in 1879, Robert Lewis Stephenson recorded his journey across France in “Travels with a donkey”; I’m guessing the donkey did most of the walking.

Pre WW2 – Growing popularity amongst the lower classes, but access is limited.

The number of ramblers increased steadily in the early years of the 20th century and by the 1930’s the activity had reached new levels of popularity, especially amongst city dwellers wanting to get away from it all. Any weekend some 10,000 ramblers could be found in the Peak District, while in the country at large there were over half a million.

In the 1920’s several economic factors led to this boom – a steady reduction in working hours, a rise in real wages and a decrease in the cost of travel. In the 1930’s a rise in unemployment added more folk with an (unwelcome) increase in leisure hours. Growing media coverage of this new craze also helped popularise rambling.

In the 19th century there had been walking clubs, often founded by members of the aristocracy, but by the 1930’s those working men bitten by the rambling bug began to organise. In 1931 six regional federations representing walkers from all over Britain joined together to form the National Council of Ramblers Federations. It wasn’t long after this, in 1935, that the Ramblers Association (today known simply as the Ramblers and still ably representing the interests of walkers) was formed.

All of these new ramblers were hampered by the fact that, in the early 20th century, access to the countryside was restricted due to the enclosure movement, comprising private landlords who closed off their land to the public and in the early years of the 20th century rambling clubs began campaigning for walkers’ rights.

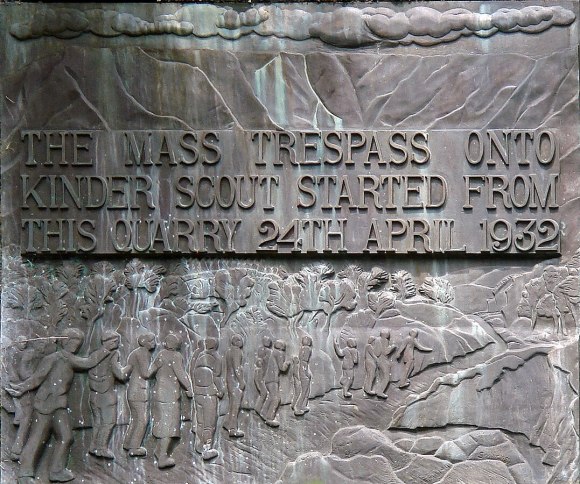

The rambler’s dissatisfaction over access rights manifested itself in more radical forms in 1932 with demonstrations and protests culminating in a mass trespass on Kinder Scout, in the Peak District. Here, the progress of around 600 ramblers was blocked by gamekeepers and scuffles ensued before they reached their destination at Ashop Head. Even though trespass was not a criminal offence at the time, six ramblers were arrested and received jail sentences of between 2 and 6 months related to violence: you might like to give a grateful thought to these heroic souls next time you traverse a public right of way or visit a national park.

A young Ewan MacColl – who was to go on to become a prolific folk song writer and godfather of the English folk revival – took part in the Kinder trespass, afterwards penning “The Manchester Rambler” to commemorate the event. This rousing anthem is sung here by Mike Harding at a memorial rally in Edale commemorating the 80th anniversary of the trespass. Go on, join in the chorus!

Post WW2 – Improved access and a further surge in popularity.

Better transport links and increased leisure time contributed to a growth in walking for pleasure in the second half of the 20th century; but other factors have also led us to where we are today.

The first influence on this rapid growth was increased access to the countryside. The Ramblers have campaigned since 1935 for walker’s rights but progress has been slow and we’ve still got some way to go on the Right to Roam, an ancient custom that allows anyone to wander in open countryside whoever owns it (the exception being Scotland where there has been universal access of land for generations). The first step in improving access came in the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 and, in 1951, the creation of the first national park in the Peak District, appropriately enough given the sterling efforts of the trespassers.

The gradual creation of more national parks and other protected land, such as areas of outstanding natural beauty and the like, have also had an impact on the take-up of recreational walking.

It was not until 2000 that the Countryside and Rights of Way Act extended the right to roam in England and Wales, although only a pitiful 8% of land in England is open to the public and access rights are more limited than in most of northern Europe. Sadly, Northern Ireland falls below even this very low bar, with relatively few rights of access for ramblers.

So, the battle to extend access rights to cover woodland, watersides and more grasslands continues. In Scotland the ancient rights of universal access were codified in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 and the Labour Party has promised that, if elected in 2024, they will legislate for a Scottish style right to roam in England. This is very good news, if it happens…..

The second factor encouraging rambling is associated with two technical innovations in communications media in the second half of the 20th century – television and the internet.

In the mid-1980’s Eric Robson presented three series of programmes following Alfred Wainwright on some of the walks he documented in his celebrated series of Lakeland guide books. Since then, there have been many TV programmes devoted to walking in the UK and further afield. Popular TV programmes include those made by Julia Bradbury and (my own favourite) Paul Rose: on radio, the “Ramblings” series presented by Clare Balding leads the field, in my view. There are lots of others, some being accompanied by books. All of this media coverage undoubtedly reaches parts of society that might never have dreamt of pulling on a pair of hiking boots: how this has changed the demographics of rambling (or not!) is considered later.

Long distance trails, often the subject of TV programmes – such as Paul Rose’s excellent documentary series on the South West Coast Path – have also proliferated, creating new horizons for those enthused by the likes of Clare and Julia.

The internet has had its impact on walking, as on everything else. Digital mapping makes it easier to plan and follow routes and share those plans with others, often via apps on a smart phone.

There are also many hundreds of blogs written about walking (like this one), along with Vlogs, videos depicting walking routes and the adventures of those following them. I share my blog on the platform formerly known as Twitter and on Facebook, illustrating how social media shares experiences and sometimes encourages others to follow suit.

Today – Walking has never been more popular, but is it still for the few not the many?

Today, walking is by far the most popular outdoor recreation in the UK. There are around 500 official rambling groups in the country, with the Ramblers boasting more than 107,000 members. Looking beyond the more committed club members, the Ramblers estimate that 9.1m adults (22% of the population) regularly walk for recreation.

The cause of the most recent surge in the take-up of rambling, indeed the largest increase in the 20th century, was the Covid pandemic: The Ramblers reported a spurt of new members between 2020 and 2021 and the charity’s Instagram following doubled over the same period. Not surprisingly, after months of lock-down, many longed to get out and enjoy the freedom and fresh air of the countryside.

An unexpected spin-off of the pandemic was that many people found travel severely restricted and discovered some excellent walks on their own doorsteps that might previously have been ignored.

So, what do todays hikers look like? In, short, there is much hard evidence to support the stereotype of the white, middle class, car owning rambler. A few years ago, you could have added “male” to this stereotype, but times have changed for the better and today leisure walking is enjoyed almost equally by both men and women. According to Sport England, women also seem to walk more often and further. Confirmation of this shift in the gender balance is the fact that today 55% of Ramblers members are women.

Sport England found that in 2009 people in professional jobs were far more likely to walk for recreation than those in lower paid work, with 28% of professionals walking regularly compared to 14% of those in manual work. To explain the reasons for this demographic, a 2009 study from the Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE) argued that the country’s poorer people are being denied access to our most beautiful countryside and missing out on the benefits that can result. It found that almost half of the most socially deprived areas are more than 15 miles from protected areas, that is, one of the ten national parks or the 46 areas of outstanding natural beauty. The same study also claimed that people from BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) backgrounds account for only 1% of visitors to national parks, despite making up about 14 % of the general population. It went on to advocate better train and bus links from towns and cities to increase accessibility for deprived and ethnic communities from the inner cities.

A 2020 article from The Guardian helps explain the reasons why people from BAME backgrounds tend not to take up hiking. The article highlights some of the “deep seated, complex barriers deterring ethnic minorities from heading out onto the fells.” Sport England identified six such barriers – language, awareness, safety, culture, confidence and a perception of middle-class stigma. Another study, from Defra, found that these communities felt excluded and conspicuous, adding that the main factors restricting use of the countryside include transport costs, lack of knowledge, and lack of a tradition of recreational walking in their cultures.

It is heartening that a number of organisations are now working to address this imbalance and overcome the barriers by encouraging these underrepresented groups to venture out and urging outdoor brands to embrace diversity.

My own observations of hiking demographics confirm all of the above: although a couple of years ago it was cheering to meet a keen rambler on Wetherlam who was sharing his enthusiasm and knowledge by organising summer camps in the Lakes for BAME kids from East Lancashire. The change that is needed will be neither easy or quick, but let’s hope this is a sign that barriers are slowly breaking down.

A recent study by the Ramblers identified the relative lack of footpaths in poorer, urban areas as a major barrier to participation by under-represented groups. The Guardian summed up their findings thus;

“The old, white, wealthy and healthy have access to miles more public footpaths in their local neighbourhoods than poorer and ethnically diverse communities in England and Wales.”

The provision of public footpaths near new housing has declined since the 1970’s: in campaigning for greater equality of access to footpaths, Ramblers have argued for stricter planning laws that require footpaths to be provided with new housing developments. In addition, they also call for existing footpaths to be protected, the many “lost” footpaths to be identified and registered and new paths to be built linking urban areas with the countryside.

I suggested earlier that the battle for access to the countryside has not yet been won. An example of the continuing struggle is the current, protracted, court cases seeking to clarify the law regarding the right to wild camp on parts of Dartmoor.

In summary, a wealthy hedge fund manager and landowner, Alexander Darwall, sought to prevent folk from camping on his land; those barred would include kids undertaking their Duke of Edinburgh Award expeditions. Darwall objected to campers interfering with the lucrative and wholesome pursuits – pheasant shooting and deerstalking – that he promotes on his land.

In January 2023, the High Court supported Darwall’s claim and held that the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 did not allow wild camping: however, on appeal in August 2023, the earlier decision was overturned. These decisions hinged on the interpretation of the 1985 Act, specifically whether “recreation” covered wild camping. As I write this, Darwall has sought leave to appeal to the Supreme Court: the Dartmoor National Park Authority has said it will defend the action.

The 1985 Act conferred access rights denied elsewhere in England, but away from Dartmoor, existing rights of access are being either denied or threatened. Eighty odd years after the Kinder trespass inspired Ewan MacColl’s Manchester Rambler, award winning folk trio, The Young ’Uns felt compelled to write another song, Trespassers, partly commemorating the earlier event, but also suggesting that the issue of access has not yet been resolved satisfactorily.

If you’ve got this far, perhaps you’d now like to turn to Part 2, where I examine how walkers’ gear has changed over the period described above.

Discover more from Over the hill - on Dartmoor & in Lakeland. I

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One reply on “Tweed suits to Gore-Tex (Part 1)”

A very enjoyable and amusing read, well researched.

LikeLiked by 2 people