- Post author By Steve Haworth

- Post dateSep 19, 2023

- No Comments on Tweed suits to Gore-Tex

The evolution of rambling gear.

In Part 1, I traced the evolution of the recreational walker from the time of the Romantic Poets to today’s internet era. Here we have a look at what they wore and the equipment they used.

18th & 19th century pioneers, making do with everyday clobber.

From whatever strata of society they came from, early wanderers wore clothing that would be considered totally unsuitable by our hi-tech standards: outerwear that wasn’t waterproof and to compound their discomfort, woollen or tweed cold weather garments that became very heavy when wet.

We’ve seen that, in the 18th century, most walkers were from the upper echelons of society: it follows that their attire would reflect their social class. In Wordsworth’s day, the typical gentleman rambler wore leather soled boots, tweed suit and shirt topped off with an overcoat or cloak, while the few ladies who rambled wore long dresses, bonnets and similar coats or cloaks. Boots were not specifically designed for walking, but were those intended for other pursuits, such as riding or hunting.

As we move into the 19th century, the attire worn by the gentry didn’t change much: while the steady trickle of walkers from the industrial working classes – seeking respite from the rigours of city life – tramped the hills in their normal workwear.

In this period, footwear was still uncomfortable, porous, heavy and – due to its lack of tread – provided no grip on wet or rough terrain. The addition of a rudimentary pattern of nails might help a bit, but the footwear still made walking hard work.

Like the industrial revolution, it can be argued that the first outdoor clothing revolution took place in Manchester. The 19th century saw the start of a process of fabric development that continued into the early 20th century; this process began in 1824, when the first “Mackintosh” raincoat was sold. This coat, made by Charles Macintosh (the K was added later) was originally manufactured in Glasgow, but by 1830 Macintosh’s company had merged with Thomas Hancock’s and moved to Manchester. Their first jackets comprised a double textured fabric sandwiched around a layer of rubber. They were initially sold mainly to the army and police forces, but also found their way to some better off individuals who proudly bestrode the fells in their “plastic macs”. While reasonably waterproof, the major drawback of these jackets was that, even with subsequent improvements, they were not at all “breathable” and therefore uncomfortable and clammy and the fabric was also easily damaged by salt and sweat.

In 1837, a Norwegian mariner called Helly Juell Hansen produced another early waterproof jacket, made of coarse cotton linen soaked in linseed oil: this was used extensively by seafarers but didn’t find its way to many walkers in the UK. However, by the time I was looking for a decent waterproof, in the late ‘60’s, the successors to the original jackets, now coated in PVC, were a best seller amongst the mountaineering fraternity. Seduced by the prospect of looking like a belisha beacon, I became very attached to my bright orange Helly; it kept me dry (on the outside at least) for the first several years of my life on the mountains. Taking off the rose-tinted glasses though, I’d have to admit it was unpleasantly, clammy and fully lived up to its nickname of “Smelly Helly”.

Pre WW2, most ramblers miss out on new innovations in fabrics and remain wet and clammy.

The early part of the 20th century, before WW2, saw the invention of a range of specialist fabrics, but these were typically developed for use by the military or expeditions, rather than the average walker. They were well beyond the price range of most people, who still tended to wear normal day clothes, cast-off workwear, or army surplus. Just after the turn of the century the average male walker would be wearing everyday trousers, a tweed jacket or blazer, hat and even a tie, while women wore dresses with Oxford shoes or sandals.

Ellis Brighams, founded in Manchester in 1933, is an outdoor gear retailer still in business today. Their website has a charming description of the founder, Frederick Ellis Brigham, attired for a walk in a trilby hat (said to be “the baseball cap of the time”), Harris Tweed suit and shirt and Scottish “beaters shoes” with tough toe springs that apparently “made striding the fells easier”. He is using a rucksack by R Burns, the best rucksack maker of the day, but now sadly forgotten.

After moving their waterproof jacket operation to Manchester, Macintosh continued to refine their designs and in the 1920’s launched their best seller, the Pakamac. This garment, made of “Gabrene”, was extremely light and packed down into a small pouch. However, it shared the drawbacks of earlier Mackintoshes – very sweaty inside and prone to rotting and disintegration on the outside. Despite this, the garment had a long shelf life and didn’t enjoy its heyday until the 1950’s and 60’s.

In 1904, as a direct response to Macintosh, another Manchester firm, Burberry, patented a breathable, lightly waxed gabardine jacket with a self-ventilating construction aimed at the whole range of country sports pursued by the upper-classes. In 1910 Robert Falcon Scott set out for the South Pole wearing a Burberry windbreaker jacket; the design of this jacket survived into the 1990’s: indeed, I recall buying a cheap copy from Famous Army Stores in the late 60’s.

Burberry’s had a competitor from East Lancashire and in 1923 the Burnley firm of Haythornthwaites created “Grenfell”, another waterproof, windproof and allegedly breathable fabric. By the 1930’s Grenfell had taken over from Burberry as the leading windproof and waterproof fabric for expeditions- although it’s highly unlikely that many of the trespassers who assembled on Kinder would have been able to afford one.

Ventile was the third high-performance fabric to come out of Lancashire. Developed to prevent airmen dying of exposure when they ditched, this waterproof and breathable fabric used long stapled cotton that kept out water when its yarns swelled.

Leather footwear with newly developed rubber soles was already making boots and shoes more durable and providing better grip on wet and rough terrain when, in 1937, one of the genuine milestones in the evolution of outdoor footwear occurred. In response to the death of friends in a climbing accident in the alps, Vitale Vibrami, in partnership with Italian rubber giant Pirelli, invented the Vibram sole, still widely used on hiking boots today. Vibrami’s sole imitated the shape of nails and was the first rubber sole to be used on specialist hiking boots.

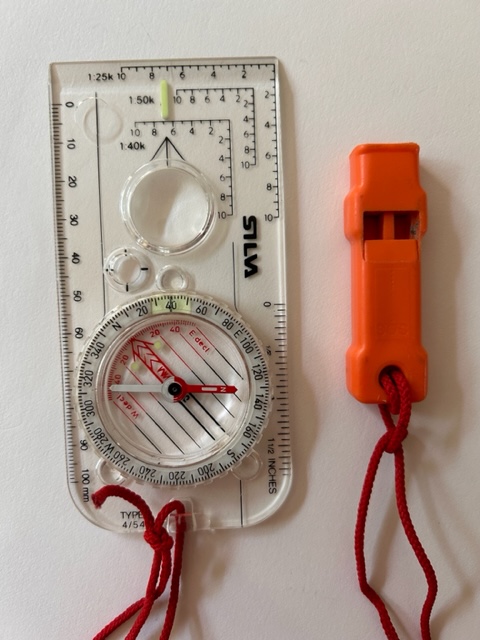

Between the wars there were innovations in outdoor equipment as well as attire. For example, in 1932 Gunnar Tillander, who founded the Silva compass company, invented the first liquid dampened compass. This improved accuracy significantly, by controlling the oscillations of the compass needle.

The lightweight revolution in clothing – layering, wicking and breathing.

In the years immediately following WW2 most walkers relied on army surplus gear, like rubberised capes, to protect them from wind and rain. By the late 50’s these had been superseded by the Pakamac, referred to earlier. The Pakamac had its heyday in the ‘50’s and 60’s, but whilst it kept rain out, it also held sweat in and so became uncomfortable to wear. Youngsters today, swaddled in their Gore Tex, will find it hard to believe that in those far off days we just accepted that getting soaked was the price we willingly paid for a good hike.

In the mid-60’s an alternative to the Pakamac was pioneered by Ellis Brigham, who added the cagoule to their range – a long garment made of lightweight PV-coated nylon made by Peter Storm. Cagoules were quite the rage, but of course we’d never experienced Gore-Tex in those simpler times.

The past fifty odd years or so has been a period of great technical innovation in the outdoor gear industry, which has responded to the demands of a growing and more affluent market by producing wave after wave of new products.

In the 70’s many walkers took to wearing sailing garments: no, not bell bottom trousers and life jackets, but anoraks like my Helly Hansen (described above). However, even with air vents the neoprene coated fabric still led to a build-up of condensation. Then in 1977 the world changed when Berghaus and Mountain Equipment launched the first Gore-Tex jackets.

In the 80’s, while Gore-Tex was steadily building its fan base, other lower-cost alternative coated fabrics – such as Entrant, Sympatex and Paramo – competed in the breathability market. By the end of the decade breathable fabrics were the norm and have remained so to this day.

For many years I was kept toasty warm on the hill by a wonderful Norwegian sweater made of oiled wool. I thought myself the height of fell-top fashion: but then fleece jackets appeared, representing another big landmark in the lightweight revolution and providing far more warmth at much lighter weight than their heavy, woollen predecessors.

Polartec fleeces were first introduced in the US in 1986 by Patagonia and a year later, in the UK, by Mountain Equipment. Other brands soon got on the fleecy bandwagon and today the place of fleece in walkers’ wardrobes is assured. Alternative, even lighter, variants involving microfibre fabrics are now widely seen on the hills, but – never one to follow fashion – I’m sticking to my original Polartec jackets for now. I detect a swing back to the “old fashioned” fleece: perhaps I’ll live to prove the old adage that if you keep something long enough, it will eventually come back into fashion?

Recently, down jackets have become incredibly popular amongst walkers (and fashionistas), although they’ve been around for a surprisingly long time. Eddie Bauer patented them in the 40’s, but they were initially used extensively by mountaineers in the 50’s: however, they are now staples of most outdoor gear ranges, providing great warmth at minimum weight. I find them a bit too warm and constricting for walking, except in the coolest conditions: although I do own one, I tend to wear it mainly for post-walk pub visits or shopping trips.

Before 1980, walkers relied on thick, baggy, tweed or corduroy breeches or trousers to protect their bottom halves. My mother made my first pair of breeches from my dad’s old tweed suit; imagine his surprise returning home from work one day to find that the bottom half of his suit trousers had been unceremoniously cut off.

Rohan pioneered the next step-change in walking attire by replacing heavy, itchy and clammy shirts, trousers and breeches with attire that did the same job at a fraction of the weight and enabled the “layering” principle to be deployed, whereby the walker can more readily adjust to changes in the weather. As an added bonus, these new-fangled garments were easy to wash and quick to dry while out on a multi-day hike. Other companies soon followed Rohan’s lead.

The advent of Vibram soles had improved grip no end, but in the late 70’s leather boots still tended to be stiff and heavy. Things improved significantly though in 1980 when lightweight fabric boots appeared in the form of the Karrimor Sports Boot, the celebrated KSB. These had a fabric/suede upper and a lightweight, flexible synthetic mid-sole instead of a stiff leather one. Having worn a couple of pairs of these wonder boots I can confirm that they were a revelation in comfort. The KSB was followed by two other contenders in the lightweight division – the Brasher boot and the Scarpa Bionic range.

The addition of Gore-Tex linings to both leather and fabric boots miraculously solved the problem of wet feet that we had previously simply accepted as normal. In the ’70’s I wore a pair of cheap, Czechoslovakian boots that I’d bought from Famous Army Stores – they looked good, but shipped water so badly that they should have been sold with free membership of a trench foot support group.

Modern walking boots are still based on the designs launched in the 80’s with the only other significant development being sports sandals, which appeared in the UK in 1992.

Today’s “must have” equipment.

As well as the revolution in clothing, recent years have seen advances in a range of equipment for the recreational walker;

- Karrimor led the way in UK rucksack design, introducing their first canvas sac in 1958 and going on to experiment with nylon in 1967. I still have a Karrimor “Outward Bound” rucksack, purchased in the early 70’s and featuring a handy, waterproof pull-out liner that created an emergency bivybag should you be caught out. In the 70’s rucksacks were still quite simple affairs, before mutating into today’s sophisticated bits of kit with padded backs, internal stiffening, zip around opening and sternum and waist straps.

- These days trekking poles are seen everywhere and I must confess that – after resisting for many years – I finally bought a pair about 5 years ago. Now I wouldn’t be without them, particularly valuing the support they give to my old, creaky legs and knees on steep descents (descents I would once have skipped down unaided, or so I tell myself). What are now seen as essential items were only introduced to a leg-weary public in the early 90’s. Initially most walkers only used one (as I still do) but now the vast majority double up, sometimes giving the impression of skiers who haven’t noticed that the snow’s melted.

- Another accessory that wasn’t much in evidence when I first wandered the Lakeland fells is the battery powered headlamp. The first headlamp was launched in 1952 by the French company Pile Wonder. Another French company, whose name is now synonymous with the headlamp, Petzl, was created in the mid-70’s by caver Fernand Petzl.

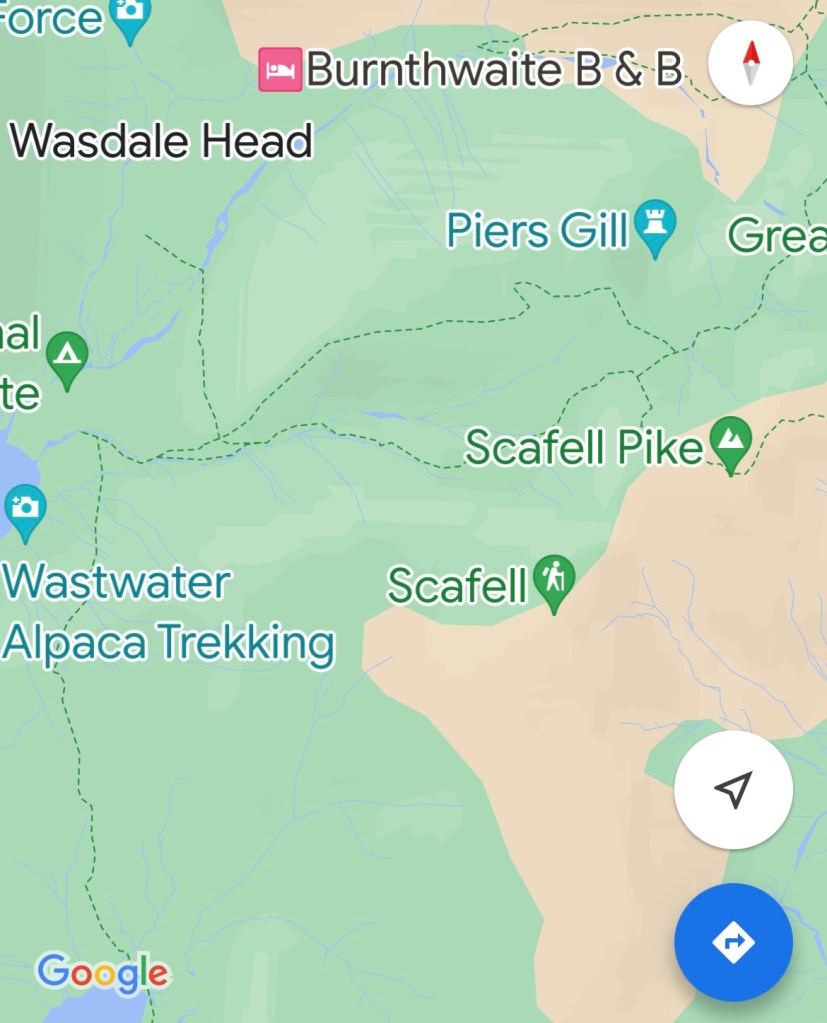

- The early 90’s saw the introduction of the GPS, with associated digital mapping that could be perused on a laptop. I resisted this aid to planning and route guidance for many years, but am now a true believer. Today the separate, hand-held, device is complemented by the more convenient, but less robust, smart phone app. That we should use smart phones with care for navigation was brought home to us recently on High Spy in the Lake District, when we encountered a likeable group of lads on their first expedition into the mountains. They were perplexed as to their position or the route to their destination-when I asked if they had a map, they proudly confirmed that yes, they were using Google maps. Not to be recommended, as I’m sure many Mountain Rescue Team members would confirm from their frequent experiences of rescuing hapless hikers attempting to navigating the high peaks with a road map.

So, after initially greeting some of these new bits of kit with incredulity (or even ridicule) I gradually came to embrace them. To bring us up to date, I’ll now look at some other weird and wonderful gear (and its old school equivalents) currently on offer, but which I haven’t yet been tempted by; however, while this kit may now elicit a “wtf” from me, who knows? Perhaps in a year or so you might find me in the middle of winter sat on the top of Blencathra, toasting my backside on a rechargeable seat warmer.

| NOW | THEN |

| Trek Umbrella – £21 | Not such a new idea this – years ago Nicholas Crane, as a bit of a gimmick I thought, used one on many of his TV travelogues, rain or shine. A mate of mine produced one on Ryders Hill, Dartmoor about 30 years ago to ward off the sun during a 32 mile north-south hike. It may have been effective, if a little cumbersome, but was it worth the ridicule to which he was exposed for many years afterwards? |

| She Wee Extreme – £11 A “Female urine device” “One size” with an “extension pipe” (best not to ask!) | Female members of the group would discretely disappear to the bushes, while less gentlemanly or ladylike companions sang ” we know where you’re going”. We made our own entertainment in those days. |

| Ezy Dog Snack Pak-pro treat bag -£37 | Dogs were thrown a bit of your lunch, or if they were lucky, they’d get chocolate drops from a plastic bag. |

| Ruffwear – Dog Cooling Vest – £85 Soak it in cold water then make your dog wear it; sounds pretty cruel to me, but apparently, it’s a “must” in warm weather. With “tripled layer SWAMP COOLER Tech”, whatever that is? | I used to go running with a pal and his dog in the forests of the Haldon Hills, near Exeter. Afterwards we repaired to the Turf Locks pub on the canal for refreshments. Here my mate would unceremoniously throw his steaming mutt into the canal to cool him down and remove the dirt he’d acquired on the trail. I wouldn’t advocate this practice, as I don’t want to get in bother with the RSPCA, but the dog didn’t seem to mind and in fact appeared to expect and indeed enjoy the experience. |

| Rechargeable Hand Warmer – £30 “… a critical accessory to have when facing the harsh reality of the elements”. | You can get a very nice pair of gloves for £30. |

| Solar Panel – £110 “Charge your phone anywhere the sun shines”. | We had batteries. The English Lake District is one of the wettest and cloudiest (as well as most beautiful) of places, so you’d be wasting your time with one there. In fact, you’d literally be “sticking it where the sun doesn’t shine” |

| 1 litre water filter bottle – £60 | We boiled water (sometimes) or, if you were fussy, you might add chlorine tablets (still available at £4 a time). Cheapskates added Iodine tablets instead, perfectly fine if you didn’t mind your tea tasting like it had been brewed with iron filings. |

| Rechargeable Heated Seat Pad – £60 | We accepted that the joys of a crisp, sunny day on the fells in winter was worth chilled buttocks. The more delicate would wear long-johns. |

| Hound Dog Saddle Bag – £41 | Would be regarded as cruelty to animals in my youth. I saw a Labrador with some wild campers on Dartmoor recently and he seemed to be struggling under the weight of a bigger pack than his master. |

| Barefoot Trail Running Sneakers-£140 The Primus Trail II is “for wide-ranging trail adventures that bring you closer to earth”. | Not looking forward to the launch of bare-ars*d trousers! |

Boom time for purveyors of outdoor gear, hikers as the height of fashion.

While I’ve been a walker, the nature of outdoor gear retailers has also changed, from the rather shabby, downmarket stores selling army surplus in the immediate post war period to the modern stores, or should that be “boutiques”, that we enjoy today, selling up-to-the-minute designs in the latest fabrics.

In my hiking life I’ve travelled from one end of this quality spectrum to the other.

My early gear was all purchased from the Famous Army Stores, which were ubiquitous when I was growing up in Lancashire, but sadly went out of business in 2002: their demise being precipitated by the foot and mouth epidemic, which had closed the countryside in 2001.

As I became more affluent (and more snobbish about gear) I progressed via Blacks of Greenock to Rohan, Mountain Equipment and other high-end retailers: I still wear a Rohan “Hyde Windshirt” that I bought over 40 years ago, attesting to the quality of the product. When I asked in the Keswick shop why they don’t sell something similar today, the assistant said something about it being “superseded” and then pointed to a framed Windshirt adorning the wall of their shop as part of a history of their wares. I felt like a museum piece, like my shirt.

Here’s a picture of my Windshirt, still going strong, my Karrimor “Outward Bound” rucksack (see above), my original ’60’s ice axe and another museum piece who’s not worn quite as well.

I’ll close by reflecting on a few eye-watering facts. According to a 2019 survey, the global hiking equipment market size was estimated at $4.5bn. Nearer to home, I recently counted 16 outdoor shops in Keswick and in his fascinating and highly recommended gazetteer of all things Lakeland, “The Lake District – in 101 maps and infographics”, David Felton notes that between the 1930’s and 2018 the number of outdoor shops in Ambleside increased from 9 to 25. Hiking is clearly very big business. In addition to the physical shops that adorn every High Street, there is also a thriving trade in outdoor gear on the internet.

The growth in the outdoor clothing market partly reflects the diversification of products from strictly functional to general purpose, travel or fashion garments. Once outdoor clothing and fashion were seen as polar opposites, but there has been a convergence in recent years. Among the many examples of products that have crossed the divide between functional and fashion and are seen just as often in the pub or supermarket as on the hill are fleece jackets, trail shoes, rucksacks and down jackets. Who knows where it will all end? Perhaps fellside-fashionistas will soon be as proud to flash their RAB base layers as their Calvin Kline underpants?

SOURCES

There is a wealth of material available on the internet and I have drawn on it freely and gratefully when writing these two posts. There follows a list of those sources that I have found most helpful:

People

- Wikipedia – various pages, especially “Walking in the United Kingdom”, “The Ramblers”, “Freedom to Roam”, “William Wordsworth”, “Hiking” plus pages on various retailers.

- The Ramblers: Britain’s walking charity

- “William Wordsworth: The man who walked a lifetime”- KenZurski –William Wordsworth « UNREMEMBERED (unrememberedhistory.com)

- Climbing with Dorothy: the Wordsworth who put mountaineering on the map (manchester.ac.uk)

- Walking with Wordsworth on his 250th birthday (theconversation.com)

- Rambling: A Short Walk through its History | Blog | World of Camping

- Whitest parts of England and Wales have 144% more local paths, study finds | Communities | The Guardian

- ‘It’s for the people’: wild campers enjoy court victory on Dartmoor | Access to green space | The Guardian

- England’s national parks out of reach for poorer people – study | National parks | The Guardian

- The BAME women making the outdoors more inclusive | Health and fitness holidays | The Guardian

Their Gear

- Chris Townsend Outdoors: How Outdoor Gear Has Changed Since 1978

- Waterproof Jacket Part 2 (outdoorgearcoach.co.uk)

- What Did Hikers Wear Before Synthetics Were Invented? – Arms of Andes EU

- Our Heritage | Ellis Brigham Mountain Sports (ellis-brigham.com)

- Rohan – Outdoor & Travel Clothing Specialists

Discover more from Over the hill - on Dartmoor & in Lakeland. I

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.